SEARCH STRATEGY

January 2017

During the second half of the year, the Partnership made one new investment and sold an existing holding. Keeping the portfolio around ten positions reduces complexity and allows me to thoroughly understand each investment, while still maintaining a comfortable level of diversification. Edward Tufte, an inter-disciplinary scholar of information design and political science, has said, “Clutter is a failure of design, not an attribute of information.” I couldn’t agree more.

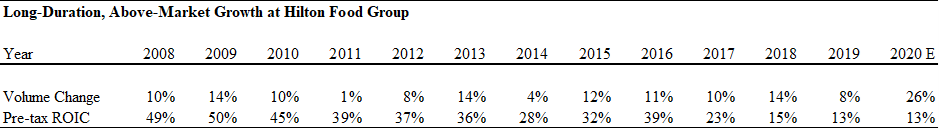

During 2016, Hilton Food Group, our UK listed meat packer, achieved its twelfth consecutive year of volume growth. A prominent element of the Partnership's concentrated investment strategy is a preference for companies like Hilton that create value in a stable, consistent manner.

Firms like Hilton operate successfully even in harsh economic conditions. While Hilton's results may be temporarily suppressed below their long-term potential in such conditions, the company has the staying power to outlast a downturn more effectively than its less resilient competitors. By focusing on superior, well-capitalized, high-return businesses like Hilton, the Partnership seeks to protect its fortunes from the vagaries of the unpredictable future.

However, when looking for new investments, I don’t start by running an automated screen for twelve years of continuous growth, or any other formulaic combination of quantitative financial metrics. Historical financial ratios can be misleading indicators of current business quality and future operating results. Nor do I begin by flipping through the daily 52-week low list for cheap stocks. While our new investments might show up there, most 52-week lows aren’t companies worth owning over a five or ten-year horizon. If one assumes that investing knowledge is cumulative, but also that it’s impossible to truly follow more than, say a hundred companies, these search strategies seem short sighted for a focused portfolio.

Instead, I prefer starting with “A” (for example, Aalberts Industries NV) and working my way to “Z” (Zytronic plc). I use simple frameworks to identify companies with business attributes that are sustainable and scalable. When these qualities combine with a capable management team making thoughtful operational and capital allocation decisions, a closed loop of cash generation, redeployment, and value creation forms. It compounds wealth over time without the need for frequent portfolio changes. In this way, I focus on the inputs, not the outputs. Eventually, the inputs should determine the outputs.

Although time-consuming, this method is a rewarding way to find companies. I benefit from having few distractions and having read about the same universe of businesses for a long time. Today, I keep tabs on about one hundred companies, or approximately 3% of listed stocks in Europe. Some would pop up in quantitative screens (e.g. Swedish Match), while others probably would not (e.g. Cairn Homes, Addlife, or Wizz Air).

By studying a limited subset over an extended period of time, any personal infatuation I initially felt with these companies’ recurring revenue, high margins, or float has, by now, worn off. The inherent qualities remain appealing, but the businesses don’t feel new, or limitless. Scuttlebutt research has identified the non-“Porter’s Five Forces” risks (e.g. the wrong people, questionable accounting, or legal and regulatory question marks) that crop up in certain excluded companies. I have also developed a greater appreciation for the management, culture, and customer relationships at some companies where the business description, industry topography, or financials don’t simply jump out at you.

In the case of Hilton, for instance, the company fits my framework for a business with a low-cost position in a large, fragmented industry producing a commodity product. Consequently, it has been able to gain market share and grow at a faster rate than its peers. While competitors are barely earning their cost of capital, Hilton earns a very acceptable rate of return.

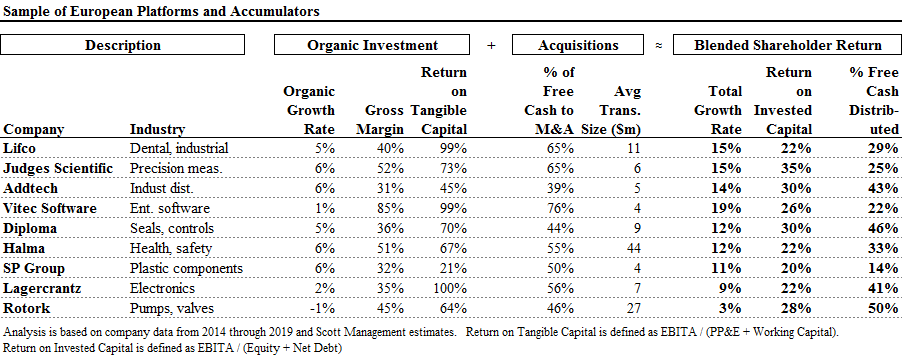

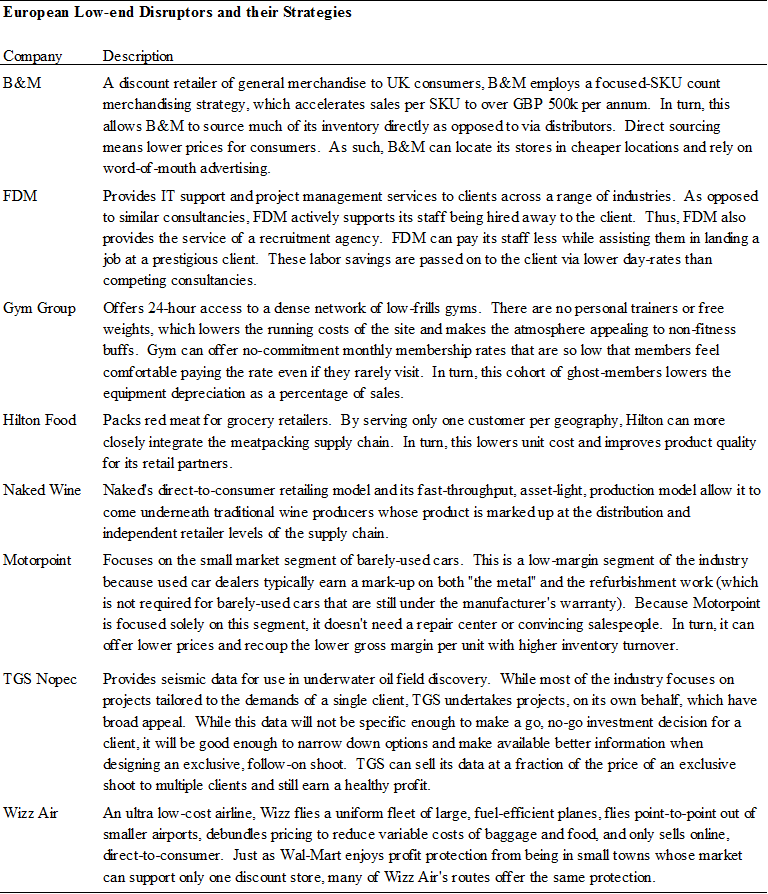

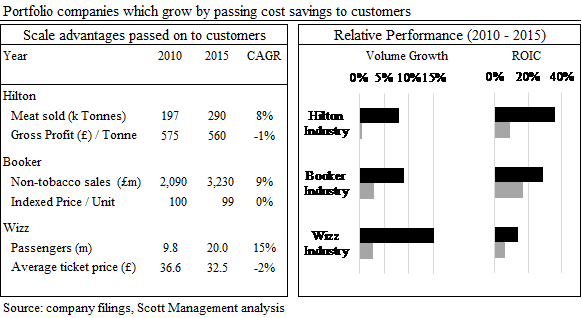

The figures below include data on Hilton, Booker, and Wizz – each portfolio holdings which follow this model. They optimize for unit cost and then offer low prices to attract volume. As output grows, they cut prices further, bolstering relationships with customers. All the while, they continue to earn a return on invested capital (ROIC) that is superior to their peers.

Dolly Parton once quipped, “It costs a lot of money to look this cheap.” The founders of these companies had some version of this focus on unit cost, drive down price, broaden market share - script in their minds at the outset and have continuously invested in realizing their vision. Once a low-cost producer in a stodgy, commodity-producing industry, unleashes a zeal for using price to stimulate demand it’s tough to stop them from steamrolling the competition.[1]

I spend my days looking for and deepening my knowledge about companies that embody this and other frameworks. Watching and waiting, we buy them under a few scenarios.

· Sometimes, investors get flighty about a short-term problem. We can take a position based on a long-term expectation while others are rushing for the exit. Our buy of Wizz Air fits with this description.

· At other times, a stock can go nowhere for a few years while the business continues to develop its cash flow and balance sheet at a healthy, but not attention-getting, clip. Eventually, like a base-runner taking a lead off first, the future return can sneak into a compelling territory. Hilton, Swedish Match, and Vopak fell into this camp.

· I also keep an eye out for businesses that should accelerate, but where the change is not yet showing up in reported numbers, analysts’ financial forecasts, or the stock price. CompuGroup Medical and our most recent investment match this scenario.

· Lastly, sometimes newly listed, spun-out, or restructured companies, can be left in a void of readily available information or a region of institutional breakdown which causes the market to become inefficient. When investing in Cairn Homes, I described why investors would, by nature, have difficulty buying at that time, regardless of price.

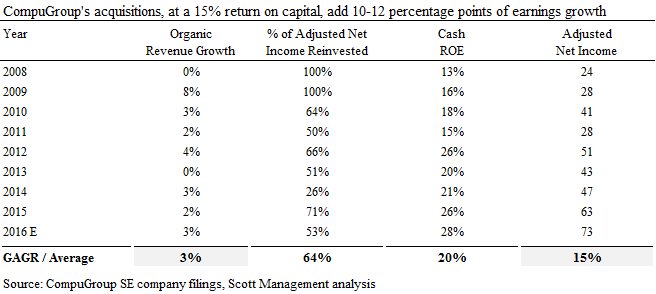

Getting back to frameworks; consider portfolio company CompuGroup. It’s a mature business which is growing, but not fast enough to attract fresh competition, and where rivals have difficulty achieving scale. This creates a natural barrier to entry, rapid returns on capital, high operating margins, significant free cash flow, and opportunities for CompuGroup to make peripheral acquisitions of companies with disproportionately high operating costs.

The historical metrics in the table below illustrate the attractiveness of CompuGroup’s model:

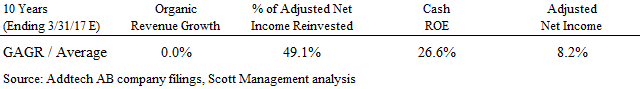

Over the period, CompuGroup reinvested 64% of its net income, achieving roughly a 19% rate of return– (15% - 3%) / 64% –and boosting net income growth by 12% annually. Another holding, Addtech, operates a very different business model compared to CompuGroup, but it follows a similar framework for redeploying earnings.

As an industrial distributor, Addtech functions as an intermediary in fragmented, low growth industries where a lack of available structural competitive advantages means it is hard to steal market share rapidly. But a focus on culture, business processes, and execution allow the company to churn out fantastic capital returns. Addtech’s comparable numbers [2] are:

I mention Addtech because, while I prefer outstanding companies, the portfolio is not necessarily a “top ten” list of businesses. Valuation matters–a lot–and it’s a mistake to disregard price, even for the best business. While an industrial distributor like Addtech might be an inferior business to say, French cosmetics giant L’Oreal, there’s nothing wrong with workhorse investments, if market prices warrant it. As former world number one tennis player, Pete Sampras once remarked, “I never wanted to be the great guy or the colorful guy or the interesting guy. I wanted to be the guy who won titles.”

A third framework the Partnership uses sketches out companies that can substantially increase the user value they provide to customers and, consequentially, can raise prices without imbalancing the customer contract, both written and understood. This is a rich source of value creation. Though not exclusively, many companies that fit this description are associated with expanding networks, where the service becomes more valuable as the number of users increases.

The Partnership recently invested in an enterprise software company which is in the nascent stages of an operating environment migration which will bolster prices. Because of its early entry into the market and local aspects of its business, it is dominant in its regional market.

The company’s revenue mix is shifting from a traditional, on-premise software model to a cloud model. The latter has several customer benefits. Client-side hardware is “thin”, reducing wasted computing power and expense. Bulk-purchased licenses, where many seats or features often remain unused, are replaced with an à la carte pricing where customers only pay for the software which is consumed. Finally, because upgrades and reliability are ensured centrally, at the hosting site, it's not necessary for customers to staff an in-house IT support team for fixes and improvements. In certain industries, such as retail, with its dispersed network of numerous locations, the benefits of these differences are profound.

These benefits are shared between the software provider and the customer. As such, revenue per customer increases. Over ten years, at our holding, I estimate that revenue per cloud customer should be 40% higher than a comparable on-premise customer. Operating costs increase due to hosting, but track well behind the revenue uptick. The profitability should increase sharply.

This transition should be treasured by shareholders. However, accounting standards muddle the picture. For on-premise software, customers pay an amount, call it 100, in the first year for the license and 18 in each subsequent year for maintenance updates. For cloud-based software, customers pay roughly 35 every year for a package that bundles the license, maintenance,and hosting (i.e. hardware). As the income statement captures what occurs in a single period, as opposed to a lifetime value, the transition has a depressing effect on revenue growth and profit margins.

This dynamic is hopefully creating an opportunity for the Partnership. Making some assumptions about normalized profitability and excluding cash, we invested at a mid to high single-digit earnings yield. From a point-in-time perspective, maybe not statistically cheap. But, when considering the durability of earnings and looking from a rate of return perspective, it’s compelling. Earnings are fully distributed to shareholders - while the capital-light model does not restrict sales growth,which measures approximately 12%.

This distribution policy is commendable, if not, at times, overly-conservative. Our holding is still run by its founder. A downside of many capital-light businesses which throw off a lot of cash is a propensity for appointed management to spend it foolishly – destroying value for shareholders. Though widespread in the software industry, our owner/operator doesn’t seem to be wired this way.

Case in point: intangible assets as a percentage of sales at the company are 2%, which compares favorably to the same metric at a few of the large enterprise software companies such as Microsoft (26%), IBM (44%), and SAP (130%). This divergence suggests that profit margins may be understated at the Partnership’s holding and that management is less likely to make poor acquisition decisions.

……

It’s worth stepping back from the trees (companies and frameworks) and reiterating what should drive Scott’s results from a forest-level perspective. The Partnership’s three operating principles are(i) a focused, value-oriented, investment approach; (ii) an equitable fee model; and (iii) transparency, governance, and alignment of incentives.

The Partnership will close to new LPs at an amount where we preserve a clear size advantage – we will be able to invest in $100m market cap companies as easily as we can invest in $100bn market cap companies. As the Partnership matures, additional capital can be accepted opportunistically, but it will be from existing LPs as opposed to new investors.

Our partners have permanent capital and think the way I think. They encourage me to focus on the destination,putting one step in front of the next, as opposed to asking what has been achieved this quarter. I’m grateful to have partners that reinforce the mindset that it’s a marathon, not a sprint.

These attributes are no guarantee of success, but they significantly increase the chances of the Partnership reaching its goals.

Edward Tufte, discussing his unconventional decision to self-publish his first book in 1983 (five thousand were originally printed and, by now, over a million have sold), wrote “My view … was to go all out, to make the best and most elegant and wonderful book possible, without compromise. Otherwise, why do it?”[3]

[1] If you’ve never heard Southwest Airlines’ charismatic founder, Herb Kelleher, discuss the airline’s history and its use of low prices to win customers (Wizz copies Southwest), this recent “How I Built This” podcast is entertaining and informative: https://www.npr.org/player/embed/502344848/502624633.

In it, Kelleher recounts his message to employees, “Think small and act small,and we’ll get big.”

[2] (keep in mind that unlike CompuGroup, Addtech’s results were affected by an unusually fierce industrial down cycle which had a depressing effect on organic revenue growth during the displayed period. Over a more normal cycle, Addtech achieves organic revenue growth closer to 3% per annum.)

[3] Tufte, Edward R, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (Graphics Press, 2001), Introduction to the Second Edition.